“The sense of place and embeddedness within local, mythical, and ritual landscapes is important. These senses of place serve as pegs on which people hang memories, construct meanings from events, and establish ritual and religious arenas of action.” Stewart and Straethern in Landscape, Memory and History

At the time of writing, there is a surge of activity ongoing across Britain to upset oppressive ways of inhabiting the land and repair human relations to the more-than-human world. Led by decolonial and feminist philosophies, as well as historical and spiritual methods of land stewardship, this activity is opening up space for more liveable futures1. A common thread running through all these projects is a recognition of the mutual needs for a spiritual and material grounding in the natural world, and new, radically inclusive commons. Through this materialisation of ecological philosophies, tangible pathways are being constructed towards food and land sovereignty for all, and the lessening of environmental destruction.

In this article, I take up the fields of landscape and nature photography2. By analysing them through a decolonial and posthumanist lens, I begin to consider how these fields could attach to, and propel, this ecological movement. Through a series of images, I hope to convey that these fields have the affective potential on subjectivities to aid in the aforementioned movement, yet in their contemporary modes they are trapped in cycles of inaction due to a reliance on historically violent ways of seeing and being with the natural world.

This essay pays close attention to the figure of ‘the photographer’ in the social imaginary of these fields. As a corresponding aim, I hope this essay aids towards the ideation of a multiplicity of new, more inclusive figures of ‘the photographer’.

The images I have collated revolve around a particular piece of land in Dartmoor; Vixen Tor. Their choice was in part guided by two theories: Katherine McKittrick’s decolonial analysis of the perspectivism in ‘Traditional Geography’ in Demonic Grounds, here transposed to the contiguous field of photography of the land, and Joanna Zylinska’s posthumanist critique of contemporary photographies in Nonhuman Photography. Our movement through these images will be guided by a story from the folklore of this area; the story of Vixiana the Witch of Vixen Tor.

As it would be an overreach to try to condense an analysis of these fields into a short essay, I’ve chosen a style of writing that is, in a way, photographic. Following this, description is generally preferred over argumentation, and the persuasive force of the writing lies in the composition of these images, the threads they bring together, or gather up from these photographic fields. Since much of my work is descriptive, understanding is sometimes left in shadows in the text, so you might have to bring yourself to the images to make some understanding with them.

Photography of the land after Enclosure:

“All I know is, I had a cow and Parliament took it away from me.” A nameless commoner (Linebaugh, p.145, 2014)

Let’s start, above the Tor and above Dartmoor, on a passenger plane, flying into England in 2003 on a clear day in summer. In this first image there is a child at the window seat marvelling at the ground below, at the fields and hedgerows that create a patchwork of vibrant greens. They are looking at the Great British Countryside that they’ve heard of in storybooks and conjured in their minds eye. Others on the plane share the child’s enthusiasm, and a ripple of remarks flows around the place about the beauty of this country.

Having started at a national scale let’s now be a bit CSI, and zoom into this image, to see what is happening at the same time down on the ground at the Tor. With the detail only imagination can afford us, we find a couple of pick-up trucks and a few men who are erecting signs and fences around the Tor. There is a new owner of this land who has recently enclosed 360 acres that surround the Tor, making it legally inaccessible to the public. She is busily ensuring that the Tor is clearly marked to reflect her legal ownership.

Today, in 2021, Vixen Tor is often also referred to as the ‘Forbidden Tor’3. There are two particularly modern tensions the hold here, one in the naming of the land, between the vixen and the forbidden, which will be explored late, another between the aestheticization of enclosure in the social imaginary, viewed from a perspective above ground, and the lived, grounded reality of enclosure.

As Peter Linebaugh writes, enclosure in England has been ongoing since “the thirteenth century, before reaching one peak during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and then another during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The extension of cultivated land and the concentration of ownership in the hands of a minority went together… As late as the end of the seventeenth century, for instance, Gregory King estimated that there were twenty million acres of pasture, meadow, forest, heath, moor, mountain, and batten land in a country of thirty-seven million acres. Even if common rights were exercised in only half of these, it means that in 1688 one quarter of the total area of England and Wales was common land.” (Linebaugh, p.144, 2014) Subsequently, violent acts of parliament throughout the 17th and early 18th century enclosed vast swathes of land. Open field villages were done away with and replaced with hedgerows and fences, a form of land management, private and enforced by law, amassed power and wealth for a select few. By 1874, 29 years after the Great Inclosure Act of 1845, only 2.5 million acres of common land remained. “The 1955 Royal Commission on Common Lands introduced a third legal party in addition to the commoners, namely, the public. Although this recognised “a universal right of public access on common land”, the public significantly does not manage the land, as commoners used to do. (Linebaugh, p.145 2014)

Through the enclosure acts and the establishment of our modern land structure, the material reality of commoning in the UK was significantly diminished, and with this the idea of inhabiting land through collective stewardship has been brought to the severely restricted. In recent history, rights to commoning has stood outside of the Overton window of political discourse. Dartmoor helps mark this trend. By 2020, you, now known as a member of the public, can only access 8% of the land in Britain, and your ability to have mutual and collective stewardship of the land, your ability for commoning, has all but vanished. Dartmoor is one of these accessible sites, and one of the main expanses of moorland left in the country. And in the shrinking legal rights the public has with land, Dartmoor is significant since it is the only place in England that remains where you can camp wildly4.

Enclosure is a very British way of managing the land, that has been entrenched for centuries. The land of Dartmoor is thought to have been enclosed directly from forest and moorland, and did not pass through a common-field stage. So it was mostly unaffected by the enclosure acts since the 17th century. We can see this in the difference between the geography of the enclosed fields near Dartmoor to those in central England. Near Dartmoor, the enclosed fields are much less uniform, and so the roads in the area are winding, unlike the straight roads of areas of England that were affected by the later, institutionally planned enclosure acts. (Hoskins, p.102, 1955)

So, we are situated in a time when ownership and possession dominate our ways of relating to the land. In 2021, a small group of people, mostly white, still have control of the land in Britain, and many of them are from aristocratic families who have dominated the land for centuries. Yet there is at the same time we are also in a time where there is an ongoing refusal for continuation of these oppressive, exclusive, ways of inhabiting land, and movements towards inhabiting the land through collective stewardship, inspired by other cultural ways of inhabiting the land.

How can we approach photography of the land from this position of enclosure?

My method will be to step outside of the present for a while, to a folk tale in an ambiguous time before photography. From there I’ll trace my steps back through the tale and through the circularity of time that lays beyond a modern perspective, stopping off at the crucial points in the story and learning from them with the help of the decolonial and posthumanist theories of Zylinska and McKittrick. Once I’ve made my journey back to the start of the story, enough should be in place to generate ideas of counter-photographies of the land.

Vixiana, the Legendary Witch of Vixen Tor

Figure 1. At the centre of the image is the rock formation of Vixen Tor which loosely resemble a woman’s head.

Between the towns of Tavistock and Princetown lays one of the largest rock formations on Dartmoor. A burial site from the Bronze Age, and possibly a druidic ritual site, set above a bog named Vixen Tor. Legend has it that an old witch named Vixiana lived in a cave at the foot of the Tor for many generations.

She was a sight to behold, standing at over six feet tall, with eyes as deeply green as the moss in a featherbed. As generations passed by, the witch remained as old as ever, never changing, never passing on. She was tall and thin as a gnarled beech branch, and her skin was just as rough5. When she opened her mouth it revealed only two rotten teeth in the shape of peat knives that protruded over her bottom lip. Some say she smelled so rancid that even the sheep of the moor would scatter when she passed. A fearsome character, one of her great joys was to thwack the eggs of moorland birds with her stick. Down the valley, people would hear her cackling throughout the day.

At sunset, she would climb atop the tor and sit on the summit looking across the moor, spying out victims for her dastardly games with a penetrating gaze. If a godforsaken traveller was unfortunate enough to pass too close to the tor, she would cast a spell across the land, creating a thick blanket of moorland fog to form around them. Even for the hardiest of travellers, this fog was too much. Once it had enclosed around them, they would quickly become completely lost. At this point, the witch would call out to them, feigning help, pretending to be a guide to safety. “Follow my voice” she would call “there’s a sturdy path just this way…”

The traveller would follow her calls, oblivious to the fact that she was leading them to a most dangerous bog, the bog that lay beneath the tor. Now their steps were numbered, as after a few footholds on solid ground they would surely fall into the bog.

Once they fell, the traveller would call out for help, as the bog started to suck them into its depths, and at this moment Vixiana would cast another spell to disperse the fog, giving this cruel witch the enjoyment of watching them slowly drown in the filthy mire, cackling as they went.

For years and years, locals avoided the route in front of Vixen Tor. Viviana had only a few travelers to prey on and became increasingly resentful. Something needed to be done.

From a nearby village, there was a young handsome man who had a deep and vengeful hatred of witches and had no fear of anything in the world. He had heard of Vixiana’s reputation all his life and promised to himself that if she was real, he’d bring an end to her spiteful life. Once, the man rescued some piskies from boggy waters, and in return, the piskies gave him two gifts. The first, a magic ring that made the wearer invisible to all regardless of who they were. The second, the gift of vision that could penetrate even the densest of moorland fog6.

And so, one day soon after this he decided to take a walk over to the Tor, on the old track that runs across the bottom of Vixiana’s lair, to see if what people told about her was true. As the stories foretold, that day, Vixania was sitting on top of the tor looking out for any unsuspecting travellers. The sight of the young Moorman sent a rush of joy through her veins, she could not wait to hear his screams of desperation as he slowly succumbed to the depths of the bog.

So, she cast her spell that brought the fog down quickly onto the moors. The young man took no notice since he could see through the cloud, unbeknownst to Vixiana, who laughed to herself and waited to hear the screams of the man as he cried for help. She waited and waited

But no sound came…

With the vision the piskies gifted him, the man could safely walk around the bog and out of the fog, towards the Tor and towards Vixiana.

This enraged the witch such that she let out a bloodcurdling scream and cast a spell that brought down an even thicker fog. The young man heard this as a cue to slip on his ring of invisibility. Vixiana recoiled as he disappeared before her very eyes. She scanned her eyes across where he was before and tried to find him, screaming and howling with rage. Meanwhile, the man snuck around the bog, rapidly climbed the tor, and crept up behind Vixiana. With one swift, and easy push he thrust Vixiana over the edge of the tor. She fell spinning and screaming through the air and landed in the stinking, muddy waters of the bog below.

The man watched in delight as the bog pulled her down, lack mud slowly rising up the witch’s body until it started oozing into her mouth, deafening her screams, ending her life.

Then all was quiet on the moor. The man watched for a while to make sure the witch did not return, and once he was safe and secure in his knowledge of her death, he returned home to his village contented. The moor was safe finally…

Looking out from Vixen Tor: Stability, technology, and (in) visibility

“The term “traditional geography…” points to formulations that assume we can view, assess, and ethically organize the world from a stable (white, patriarchal, Euro-centric, heterosexual, classed) vantage point. While these formulations— cartographic, positivist, imperialist—have been retained and resisted within and beyond the discipline of human geography, they also clarify that Black women are negotiating a geographic landscape that is upheld by a legacy of exploitation, exploration, and conquest.” Katherine McKittrick in Demonic Grounds

In her critical analysis of colonial and hegemonic geographic practices, referred to as Traditional Geography, McKittrick exposes the perspectivism of this field. A perspective that purports to be the unitary, stable, or objective perspective for perceiving, understanding, and organising the world from, maintained through technological apparatuses. From the exclusionary social technology of the academy, governmental organisations, and corporate surveyors, to the material technoscientific technology of sensors, models and photographs used for cartographic purposes and for creating surveys and official records, to the literary technology that disperses these products as hegemonic (e.g. ordinance survey maps).

If you will, I’d like to position the story of Vixiana as a story of the establishment of this perspective.

A tale of the battle to reassert the order of (white, patriarchal, able bodied, Euro-centric, heterosexual, cisgendered, classed) Man over wild and feminised Nature7 via technologically enabled violence1. Through reading the story in this way, we can gather up all of the necessary parts to understand how landscape and nature photography has historically shared, and contemporaneously shares, the perspective of Traditional Geography, and how these fields perpetuate conservative and exclusionary ideas of how humans should inhabit the land, and, contemporaneously, how we should act in the face of environmental collapse.

As the Moorman looks out across the moor in Vixiana’s position of power, atop Vixen Tor, he breathes a sigh of relief. Having restored a quiet, conservative order over the land, he sits above the moor. In this story, the witch can be read as both an allegory for the wildness and chaos of the natural world channelled through the feminine body, and also of alternative, non-capitalist, non-patriarchal ways of inhabiting the land that are grounded in nature. Remember that Vixiana hasn’t aged throughout the lives of the villagers. Unaffected by the linear, arrowlike progress-time of capitalist modernity, she is timelessly old.

In the act of killing the witch, the man vanquishes both the terrifying wildness of nature, as well as the idea that humans can be grounded in nature, replacing these with an ordered, patriarchal, and violently maintained view of nature, and corresponding way of inhabiting the land. The eradicated alternatives have to be coded as uncivilised (stinky), inferior (ugly), and themselves violent (sheep-bashing) to make his violence not only worthwhile but justifiable. This echoes with the worldview and methods of the proponents of British Colonialism and capitalism, dehumanising others to legitimise their violence and domination8.

And, when nature is this way, the Moorman likes what he sees. Nature is beautiful when it is for him.

Now, the man presumably could have killed Vixania with a knife or some other weapon, but instead chooses a symbolic exit for our witch. He tosses her from her position of power atop the tor into the bog below, murdering her with her own technique. Why does the man take this action then? Perhaps it is less callous to push in the back rather than stab in the back? Partly, yes, but perhaps on top of this, the Moorman also wants the pleasure of watching her slowly descend into the bog. This move can help us to reflect on modernity if we pause for a moment on the figure of the bog.

As Stuart McLean details in his work on the Céide Fields in County Mayo, Ireland, bogs are an important archaeological site because of their preserving qualities. In Ireland, researchers have found whole villages subsumed by the peat bogs (McLean, p.48-9, 2003). With this in mind, the Moorman is not just killing the witch but is eradicating the ideas and ways of living that the witch stood for to the realm of natural history. The figure of the witch, subsumed by the bog, is the dynamic and continual process of historicising, and neutralising the historical reality of witchcraft and alternative, non-capitalist, non-patriarchal power arrangements.

The story of Vixiana, read alongside the historical story of the establishment of capitalist modernity, also helps us to understand the genealogy of contemporary photography of the land. The abilities the young Moorman uses, an inhuman clarity of vision and on-demand invisibility, afforded by the technology he possesses, are ones that still prevail in contemporary photographies of the land.

Photographies of hyper-representation, driven by an urge towards seeing the world as discrete and clear, whose images are composed such that the photographer leaves no personal mark on the images, a passive and neutral observer of Nature with an objective/objectifying gaze, rooted in the realm of culture. As I’d like to expose, by sharing the tactics of the Moorman which are suited for dominating nature, photography of the land and the more-than-human world is trapped in a cycle of inaction (shooting itself figuratively in the foot) and so, if photography of the land is to hope help engender more liveable worlds it needs to embrace alternative approaches.

The HobbyHunter: Clarity, Invisibility and Punishment

Figure 2: A man sits in full military-style camouflage covering all of him apart from a small slit for his eyes. He wields a camera with an enormous lens which is also camouflaged. He sits in a bright, leafy green woodland scene.

“I would like to insist on the embodied nature of all vision and so reclaim the sensory system that has been used to signify a leap out of the marked body and into a conquering gaze from nowhere. This is the gaze that mythically inscribes all the marked bodies, that make the unmarked category claim the power to see and not be seen, to represent while escaping representation.” Donna Haraway in Situated Knowledges

The two abilities that allow the Moorman to do away with Vixiana, and establish their position as dominant and dominating are; an inhuman clarity of vision that can penetrate even the densest of fogs, and a magic ability to become invisible when the time is right, both gifted to him by the piskies, the spirits of the moor9. These are the man’s tools, his technology if you will, and in the story of the establishment, and preservation of a modern idea of nature, technologies that afford these abilities have been key to imposing epistemological, material, and imaginative control10.

One strand underlying McKittrick’s inquiry into Black geographies in Demonic Grounds is based on her critique of the geographical technologies that afford these abilities, and use them to dominate. Photography has run a similar path historically, which enmeshes with Traditional Geography at many points, hardening its truth claims with images, and aestheticizing its perspective into ideas of beauty. Photography was brought on colonial expeditions through the 19th century, and the images created were used to form a particular, colonial, idea of the landscape for a European and United States audience (Berger, p.42-6, 1999 & Azoulay, A, 2018). This history provokes a parallel term to McKittrick’s, Traditional Geography: Traditional Photography.

So what is Traditional Photography? And what legacies has Traditional Photography left today? I’ll begin with the latter, through a figure that is loosely represented in the header image of this section, and return later to the former.

TradModern Photography of the land and the more-than-human

The figure that I’m about to introduce, I believe, gathers up much of the key aspects of prevailing photographies of the land today. Here, we find them as a hobbyist in an enclosed moor, but they might equally be in umpteen other, ‘wild’ places. In a mountain range or rainforest with a multimillion-pound funding and an entourage of assistants, or behind a desk in a control station of a techno-scientific corporate outfit, scanning satellite imagery. As you’ll note, this figure shares much with the Moorman and with Traditional Geography.

Here, I’ve gendered the figure as male which is, I think, reflective of how the photographer of the land is conventionally figured today. This is much of the problem, the photographer figured following a traditional Western humanist model which positions the white, classed, straight Man as the central protagonist11. A plurality of players are necessary to be able to return photography of the land to the goals it sets itself, and help create a more liveable world for all.

When we return to Vixen Tor in the present day, twenty one years into the second Christian Millenium, much has changed. Since the time of the Moorman, the carceral state has intensified significantly. In one of the aforementioned towns closest to Vixiana’s dwelling, Princetown, now stands a high-security prison, erected in 1809, another vessel for enclosure. When we reach the Tor, we find a man in complete camouflage lying next to the rock formation with a telephoto lens, likewise camouflaged, pointed towards the moor. The ghillie suit and lens covering that comprise the camouflage are high-grade military-level gear, making the man invisible to the majority of the mammals in the area. He lays on newly enclosed, private land. He is solitary and unreachable, invisible to the more-than-human world and to the majority of humans alike.

Let’s call him Flicker, who hobbies as a photographic huntsman. The day is just fading into darkness and he’s waiting for a rare sighting of a hazel dormouse, a speciality of the moor. His finger rests on the trigger of his camera which is set to burst mode, capable of shooting seven HD 5616 x 3744 pixel, 31.9 MB images per second once the trigger is pressed. The settings of his camera can manipulate the light to produce highly detailed images despite the dusk. The light sensor is adjusted to the lower levels of light, while the wide aperture allows as much light in a possible.

After thirty minutes in this position his hope starts to waiver, and the cold begins to weaken his grip. He shakes his handwarmers once more to get the tail-end of the ongoing exothermic reaction out into his rigid hands. Five more minutes, he tells himself, it’ll be worth it.

A few moments later his prey creeps into view, some ten meters away. Flicker shoots fifteen bursts in the time the dormouse is within the sites of the lens, a mere thirty or so seconds. In this time his heart rate has accelerated to 200 bpm which made the last two bursts blurry and difficult to make out. Shit… Flicker thinks as he scrolls through the most recent photographs of the 105 images he’s taken. Maybe his excitement got the better of him, he’s not an army sniper after all, he still gets a rush from the hunt.

However, much to his delight, after the first fifteen or so images the dormouse can be seen without blurs, a little dark maybe – he didn’t expect to be out this late and hadn’t adjusted his camera settings accordingly – but he can touch that up in post-production easy, they’ll be clear as day by the end of the night.

He’s chuffed with today’s catch, which might make the shortlist for a few nature photography competitions. So, he packs up his equipment, and heads off to upload them to his computer…

It’s significant that the prison is in our scene today. The area that Vixiana once roamed is likely now under intense scrutiny from the carceral state which, like the Moorman’s gaze, exerts a conservative order. The prison in our scene is not just reflective of the rise of carceral capitalism and enclosure as ways of organising the world, but also reflects back on photography of the land and the more-than-human world, helping us to understand the relationships between surveillance technology, photography, and enclosure. If you were to research into emergent photographic technology for wildlife and nature photography, you would not only find an abundance of military technology, camo balaclavas and hides, you would also find that these photographic technologies overlap with surveillance technologies. The companies selling CCTV cameras are now the ones selling timelapse cameras for nature photography. The technology used to help enclose people (which afford clarity and invisibility to those holding power) are now repurposed as ways of relating to the more-than-human world. Here the search for a different way of photography of land connects with movements toward abolition. Here, photography can learn from the wealth of Black abolitionist methodologies.

Much like the moorman before him, Flicker uses technologies that afford clarity and invisibility to construct and enable his view of nature. Like the witch-hunting moorman Flicker still acts like a hunter, except now he is really just roleplaying from the central tenets of masculine imagination. His hunt is less viscerally violent than his forefathers, but is entwined with military violence, dependent on the military technology of camouflage and long distance lenses. He stalks, shoots, captures, and shows off his catch, but there is no blood.

However, and this is important for constructing ideas of new photographies of the land, Flicker’s aims are different to those of the moorman. He lives after Vixiana’s elimination, and the initial domination of nature and otherness, in the time of enclosure and the Anthropocene, and with this has come some recognition of the ills of modern ways of inhabiting the land and a desire for change. Unlike the moorman, who desired to re-establish the status quo by dominating wildness, reminiscent of today’s superhero’s, Flicker seems to actually be in tension with this recent status quo. Beyond the bodily pleasure of the thrill of the hunt that satisfies his masculine desires, Flicker is presumably also motivated by some kind of love of nature, even if this is nature from and for the White British Gaze. It’s also not a stretch to say he wants ways of inhabiting land to change. He probably wants more wildness unlike the moorman, and could perhaps see himself as an activist. However, Flicker inhibits himself with his reliance on his predecessors tools and his refusal to shake off historically socialised ways of seeing, and being with, their environment.

In the contemporary figure of Flicker, the photographer is the figure of the lone male man behind a telephoto lens on enclosed land. If we are to construct new photographies, I don’t think the route is to imagine different variations of Flicker by putting this action man in a range of outfits. Instead the figure of Flicker should be decomposed into a plurality of photographic figures. However, since this figure is so prevalent in contemporary photography of the land, I think it’s useful to detail his motivations a little more, and to perhaps get Flicker on board with new ways of being with their environment, and new photographies.

I think his psychology goes something like this…

Species are dying and global warming is in effect. We need to evoke beauty and the sublime in the more-than-human world to galvanise some action! If I can demonstrate to others how beautiful these species and landscapes are, then they’ll want to change them. And when they walk through their city at night and see the haggard foxes that live among them they will know that we, the humans, have made a wrong turn and need to change our ways.

A sort of shock and awe tactic for praxis reminiscent of a Preacher trying to get others to heaven by enforcing a constant state of guilt and shame for their sinfulness, centring the problem in the masses. Although this photography might be driven by a desire for better worlds, its catastrophising tendencies, inability to point towards structural issues and possible alternatives, and placement of contemporary environmental violence’s in a generalised ‘humanity’ stops any meaningful changes from being generated in response to its images.

The hyper-representational, computationally enhanced idea of Nature this photography co-creates is an over-exposed Nature drenched in constant flashlight, where shadows and darkness have been dissipated. And without darkness, we have no night and subsequently lose the biotechnology of tiredness. But without darkness, how can we dream?

If we are to use photography to help repair relationships with the land and the more-than-human world, alternative modes are necessary…

Traditional Photography: The aestheticization of Landscape

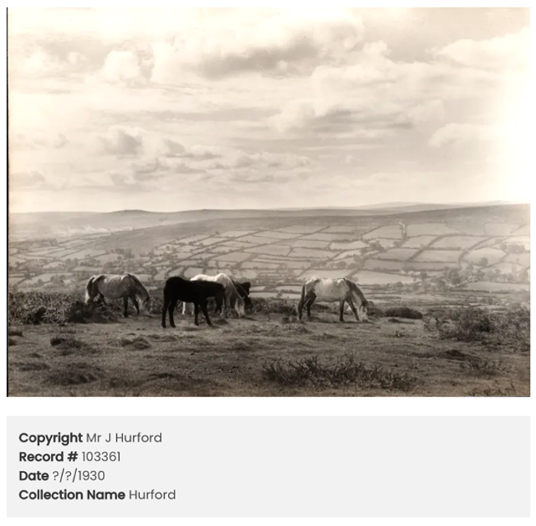

Figure 3: A traditional photographic representation of Dartmoor. The scene is composed in horizontal thirds, with a group of horses in the lower third, a patchwork of enclosed fields that roll into the distance in the middle third, and a cloudy sky in the top third. The photograph is the copyright of Mr J Hurford.

Figure 4: a tweet that contains four photographs of ‘typical’ English countryside scenes. Top-left: a fence along a road with a green field behind it. Top-right is a village with sandstone cottages along a road. Bottom-left: a castle with a well-groomed garden and a sandstone church. Bottom-right: a grassy field containing cows, in front of a village. The caption reads “Imagine hating England. There is no country in the world more beautiful” followed by an England Flag emoji.

At the end of the 19th century, there was a lively debate ongoing in Britain about the purpose of landscape photography. Could photographs be artistic, and imaginative, or was their purpose strictly scientific, used for direct representation of a scene? Those who entertained the former referred to their work as Pictorial. They embraced the soft blurs of longer exposures and deep contrasted shadows, over detailed representation. Pictorial photographers obsessed over the composition of their photographs, preferring to begin work on a photograph first by pencil and paper, to compose their scene, before moving to their camera. They carefully followed the rules of the Great Landscape painters, delicately, and some might now say scientifically, balancing their scenes for the ‘best-general-view’ of a landscape. Pictorialists worked to recongeal ideas of natural beauty and Nature from painting into photography. (Hinton, p.7-12, 1898) This approach was shared by photographers on colonial exploits, such as on expeditions to areas of natural beauty in the US (Berger, p.47, 1991). Photographers imposed the idea of a ‘best general view’ of a place.

Pictorialist aims were simple: to capture beauty and to demonstrate that photography was a worthy art form. This was the Pictorialist’s relationship to their environment. Nature as an object to be admired.

As time progressed both approaches were folded back into each other. By the 1930s Pictorialist photographers began to used the material technology of the Scientific Photographers and their landscape images took on a sharper, more detailed look. (Adams, 1931) This style required expensive photographic equipment, making Pictorialist photography mostly the hobby of wealthy men.

And here we get to the header image of this section; a landscape photograph of Dartmoor from 1931. A pastoral scene that is delicately composed into thirds with the hedgerows of enclosure being used as a framing midground for the horses in the fore. The photograph is not markedly Pictorialist or Scientific. Instead, it is a blend of both, an accurate representation of a scene that attempts to be beautiful. By the 1930’s, this type of image was being made and presented across the UK, aestheticizing the land in Britain, distilling a potent brew of beauty, landscape conservatism and jingoism. In this process, the domination of the land, and the colonial history of the countryside is concealed in ideas of beauty, the figure of the Great British Countryside.

Fast forward to 2021 and in figure 4, we see how this a very similar type of imagery can still be drawn on by the political right as a means to form national identity and to exclude. The writer of this image draws on a subconscious perception of the Great British Countryside that is in part constructed by hobbyist Pictorialist landscape photography12. The new images are not well composed, but because of the effects of Pictorialism on the social imaginary, they don’t have to be to evoke the idea of Great Britain as beautiful. Through their appropriation by the political right, these images help to code the countryside as white, perpetuating a hostile environment for people of colour (Bakar, 2020), and through their aestheticization of enclosure, they make land reform a taboo topic in political discourse.

So, this way of seeing the land in Britain and its conjoining image type needs to be upset, and this is a vital task for photographers of the land. I propose decomposition as a suitable photographic methodology for dealing with these prehended image of the land in Britain. Decomposition in both its artistic and horticultural sense, both a breaking apart of things previously composed, but also the consistent work of growing new life from deathly forms.

Ink into flesh; Technoscientific Landscape Photography and Identity

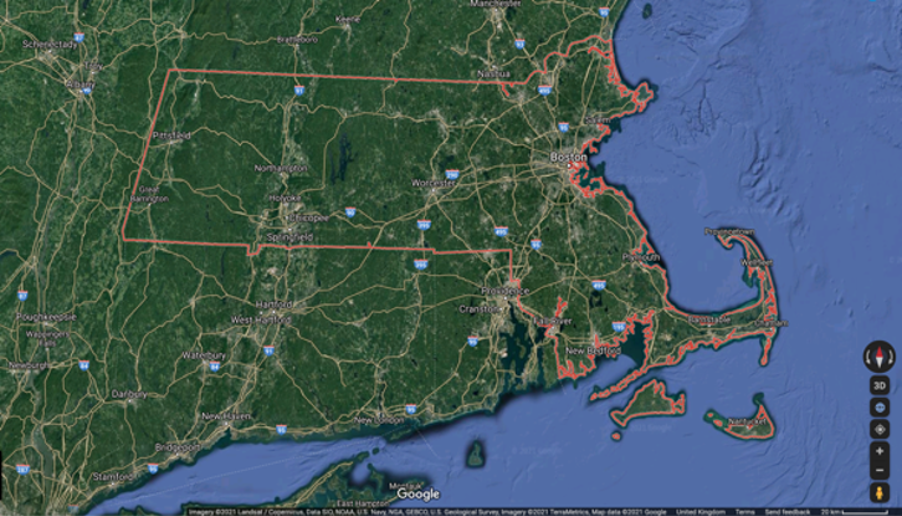

Figure 5: The landscape image shows an aerial satellite map of the east coast of America from Google maps. The state border of Massachusetts is highlighted in orange.

“Embracing nonhuman vision as both a concept and a mode of being in the world will allow humans to see beyond the humanist limitations of their current philosophies and worldviews, to unsee themselves in their godlike positioning of both everywhere and nowhere, and to become re-anchored and reattached again.” Zylinska in Nonhuman Photography

The final image I’d like to leave you with is one that gathers up the perspectivism of contemporary technoscientific photography of the land together with identity, through the landscape image13 of the border. I see this image as a symbolic reminder of Zylinska’s call for ‘re-anchoring and ‘re-attaching’ ourselves to the land, as well as the need for a plurality of ideas of what is meaningful in landscape beyond exclusive political symbols such as borders.

Again, let us return to the moor…

Last year, at the height of summer, I sat in the garden of a pub in a village just outside the south easterly edge of Dartmoor with a few friends. Our t-shirts clung to our backs as we clutched pints of cold pepsi to try to cool down. We had arrived at the midpoint in our walk, and had learned that the low-lying fauna of the moor provided too few shady spots to take shelter from the sun. As we gulped the pepsi down our t-shirts chafed against raw necks and pink forearms.

On the table next to us were a couple of families chatting, a fairly unremarkable scene. Boys debating the benefits of different toy guns with their parents. However, one image of a person from this table stayed with me after we had strapped on our hiking packs and made our way out of the village: A father in a Boston Red Sox cap, with a singular tattoo of the Massachusetts state border on his forearm, pride of place.

“you can take the man out of the state, but you can’t take the state out of the man”

United States Proverb, probably…

The tattoo on his arm is a technoscientific landscape image. In the sense that it is a constructed idea of place; Massachusetts, whereby the state is represented and reduced to its border, the constructed point where people supposedly stop being one identity and become another. What is important symbolically, is the emptiness within the border.

This is reflective of how many identify with the land today. The particularities of the landscape are pushed aside by the dominant the figure of the nation-state and its contiguous imagery. Our two key abilities still hold in this image. The claims to objectivity of technoscientific cartography and photography collide and multiply to give a clarity to the scene and to afford the claim that the scene represents a view from nowhere, despite the fact that the border is composed through a political collage. Beyond this, we see how these images carry through to constitute identity through exclusion. If images and symbols of the nation-state constitute ideas of landscape, how can those who are excluded from the nation-state feel connected to their environment and like they belong?

The task of reattaching, and reanchoring in an reparative, inclusive and humanising way is both a material and imaginative one. And if photography is to aid in this task, we need more inclusive figures of photographers, supported by alternative photographic methodologies. Bewitched-photographers, perhaps, who conjure up landscapes and new belongings with land by bringing spiritual objects together into a whole. Or drag decomposers who take established and restrictive images of landscapes, tear them apart, and reform them into something fresh. Photographic piskies, maybe, who understand and inhabit the landscape through fog and shadows. Landscape photographers led by a desire to open up constricted land, golf-courses and aristocratic manors alike…

Footnotes:

Footnote 1: Three notable organisations are: Land In Our Names (https://landinournames.community/), The Landworker’s Alliance (https://landworkersalliance.org.uk/), Agrarian Trust, (https://agrariantrust.org/), Soul Fire Farm (https://www.soulfirefarm.org/).

Footnote 2: I’ll specifically focus on the hobbyist and mainstream media sides of these fields. I use the term ‘nature photography’ in reference to popular usage but prefer the term ‘photography of the more-than-human’. The images in this piece cover their historical and contemporary modes. Elsewhere I detail emergent photographies that could aid in this ecological movement, and call for photographic methodologies of decomposition, and a return to darkness, shadows, and to the biotechnologies of tiredness and dreaming.

Footnote 3: https://www.legendarydartmoor.co.uk/for_bidden.htm

Footnote 4: Significantly, the effect of these laws are felt most by the marginalised, especially by Travelling communities whose way of life is made near impossible. There is an ongoing assault by Conservative party to strengthen enclosure by criminalising trespass. Notably, Priti Patel recently announced a strengthening of police powers and a new criminal offence to target unauthorised encampments. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-to-give-police-powers-to-tackle-unauthorised-encampments

Footnote 5: some versions of this story draw more heavily from oppressive tropes. I’ve chosen to exclude some of these so as to avoid reinforcing some of these patterns.

Footnote 6: the piskies are omitted in some of the versions of this story I’ve found.

Footnote 7: here the capitalisation refers to binary idea of Nature and Culture of scientific positivism. For an analysis of scientific positivism’s perspective on nature read here Genevieve Lloyd’s chapter on Francis Bacon in her book “The Man of Reason”, alternatively Donna Haraway’s Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse

Footnote 8: My reading runs is guided by Silvia Federici’s Marxist feminist analysis in ‘Caliban and the Witch’ which recognises that the demonisation and murder of powerful women and alternative power arrangements through the figure of the Witch as a vital stage in the development of global Capitalism.

Footnote 9: The piskies are not included in all versions of the story. I chose this version as a reminder of how these technologies are always already enchanted, despite the disenchanting claims of scientific positivism.

Footnote 10: I don’t argue directly for the importance of these abilities in the establishment and preservation of technocapitalist modernity since this has been done elsewhere in much more detail. Ruha Benjamin’s section in Race after Technology about Frantz Fanon’s analysis of the relationship between enclosure and exposure is great here. Edouard Glissant’s theory of Flash Agents and the Colonial drive towards transparency in Poetics of Relation is also relevant here.

Footnote 11: Seen Azoulay, A. (2016) Photography Consists of Collaboration: Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald, and Ariella Azoulay In Camera Obscure, published by Duke University Press.

Footnote 12: For examples of TradModern landscape photography https://www.lpoty.co.uk/gallery/2013/classic-view.

Footnote 13: Here I am extending a classical idea of landscape photography to aerial satellite and drone photography.

References:

Adams, A. (1931) Pictorial Photographs of the Sierra Nevada Mountain. Smithsonian Institution.

Azoulay, A. (2018) Unlearning Imperial Rights to Take (Photographs) (no date) Fotomuseum Winterthur. Available at: https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/2018/10/09/unlearning-imperial-rights-to-take-photographs/

Bakar, F. (2020) ‘Why Britain’s countryside is still unwelcoming for people of colour’, Metro, 21 September. Available at: https://metro.co.uk/2020/09/21/the-english-countryside-was-shaped-by-colonialism-why-rural-britain-is-unwelcoming-for-people-of-colour-13273808/ (Accessed: 15 March 2021).

Benjamin, R. (2019) Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. John Wiley & Sons.

Berger, M. A. (1991) Landscape Photography and the White Gaze. In Solomon-Godeau, A. (1991) Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices. University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, D. (1988) ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp. 575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066.

Hinton, A. H. (1898) Practical pictorial photography. London,. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044034081190.

Hoskins, W. G. (2013) The Making of the English Landscape. Little Toller Books.

Linebaugh, P. (2014) Stop, Thief!: The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance. PM Press.

McKittrick, K. (2006) Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. NED-New edition. University of Minnesota Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv711 (Accessed: 14 March 2021).

Pamela, E., Stewart, J. and Strathern, A. (2003) LANDSCAPE, MEMORY AND HISTORY Anthropological Perspectives.

Zylinska, J. (2017) Nonhuman Photography. MIT Press.